Supply-side economics

| Part of a series on |

| Capitalism |

|---|

|

The term "supply-side economics" was thought, for some time, to have been coined by journalist Jude Wanniski in 1975, but according to Robert D. Atkinson's Supply-Side Follies,[4] the term "supply side" ("supply-side fiscalists") was first used by Herbert Stein, a former economic adviser to President Nixon, in 1976, and only later that year was this term repeated by Jude Wanniski. Its use connotes the ideas of economists Robert Mundell and Arthur Laffer. Supply-side economics is likened by critics to the theory of trickle-down economics,[5][6][7] which may, however, not actually have been seriously advocated by any economist in that form.[8][9]

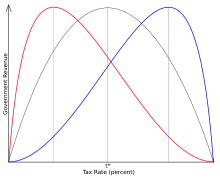

The Laffer curve illustrates a central theory of supply-side economics, that lowering tax rates may generate more government revenue than would otherwise be expected at the lower tax rate because moving off of a prohibitively high tax system could generate more economic activity, which would lead to increased opportunities for tax revenues.[10][11] However, the Laffer curve only measures the rate of taxation, not tax incidence, which is a stronger predictor of whether a tax code change is stimulative or dampening.[12] In addition, studies have shown that tax cuts done in the US in the past several decades seldom recoup revenue losses and have minimal impact on GDP growth.[13]

Historical origins

Robert Mundell

However, what most separates supply-side economics as a modern phenomenon is its argument in favor of a low tax rate for primarily collective and notably working-class reasons, rather than traditional ideological ones. Classical Liberals opposed taxes because they opposed government, taxation being the latter's most obvious form. Their claim was that each man had a right to himself and his property and therefore taxation was immoral and of questionable legal grounding.[18] Supply-side economists, on the other hand, argued that the alleged collective benefit (i.e. jobs) provided the main impetus for tax cuts.

As in classical economics, supply-side economics proposed that production or supply is the key to economic prosperity and that consumption or demand is merely a secondary consequence. Early on this idea had been summarized in Say's Law of economics, which states: "A product is no sooner created, than it, from that instant, affords a market for other products to the full extent of its own value." John Maynard Keynes, the founder of Keynesianism, summarized Say's Law as "supply creates its own demand." He turned Say's Law on its head in the 1930s by declaring that demand creates its own supply.[19]

In 1978, Jude Wanniski published The Way the World Works, in which he laid out the central thesis of supply-side economics and detailed the failure of high tax-rate progressive income tax systems and U.S. monetary policy under Nixon in the 1970s. Wanniski advocated lower tax rates and a return to some kind of gold standard, similar to the 1944–1971 Bretton Woods System that Nixon abandoned.[citation needed]

In 1983, economist Victor Canto, a disciple of Arthur Laffer, published The Foundations of Supply-Side Economics.[20] This theory focuses on the effects of marginal tax rates on the incentive to work and save, which affect the growth of the "supply side" or what Keynesians call potential output. While the latter focus on changes in the rate of supply-side growth in the long run, the "new" supply-siders often promised short-term results.[citation needed]

Laffer curve

Laffer curve: t* represents the rate of taxation at which maximal revenue is generated. This is the curve as drawn by Arthur Laffer,[21] however, the curve need not be single-peaked nor symmetrical nor peak at 50%.

This led the supply-siders to advocate large reductions in marginal income and capital gains tax rates to encourage allocation of assets to investment, which would produce more supply. Jude Wanniski and many others advocate a zero capital gains rate.[24][25] The increased aggregate supply would result in increased aggregate demand, hence the term "Supply-Side Economics".

Furthermore, in response to inflation, supply-siders called for indexed marginal income tax rates, as monetary inflation had pushed wage earners into higher marginal income tax brackets that remained static; that is, as wages increased to maintain purchasing power with prices, income tax brackets were not adjusted accordingly and thus wage earners were pushed into higher income tax brackets than tax policy had intended.[14][citation needed]

Some economists see similarities between supply-side proposals and Keynesian economics. If the result of changes to the tax structure is a fiscal deficit then the 'supply-side' policy is effectively stimulating demand through the Keynesian multiplier effect. Supply-side proponents would point out, in response, that the level of taxation and spending is important for economic incentives, not just the size of the deficit.[citation needed]

According to the Laffer Center, "the higher the starting tax rate, the more dramatic the supply-side stimulus will be from cutting the tax rate." [23] Kennedy reduced taxes from a top marginal rate of 91% to 65%,[26] which increased government revenue[citation needed]. Also, Reagan reduced taxes from a top marginal rate of 50% to 28%,[27] and saw an increase in government revenue during his term.[28][dead link] The Reagan administration and the Kennedy administration both justified such changes in socioeconomic terms by invoking the old saying that "a rising tide lifts all boats."[29]

The Laffer curve relates only real revenue to tax rates and does not make predictions about revenue as a percentage of GDP. The Laffer curve implies that when tax rates are too high, gross tax revenue in dollars may be, after a transient drop, greater after lowering tax rates, due to increased economic activity. They may also be lower or they may remain the same.[23]

Fiscal policy theory

Supply-side economics proposes that tax decreases may lead to economic

growth. Historical data, however, shows no significant correlation

between lower top marginal tax rates and GDP growth rate.[30]

Crucial to the operation of supply-side theory is the expansion of free trade and free movement of capital. It is argued that free capital movement, in addition to the classical reasoning of comparative advantage, frequently allows an economic expansion. Lowering tax barriers to trade provides to the domestic economy all the advantages that the international economy gets from lower tariff barriers.

Supply-side economists have less to say on the effects of deficits, and sometimes cite Robert Barro’s work that states that rational economic actors will buy bonds in sufficient quantities to reduce long-term interest rates.[31] Critics argue that standard exchange rate theory would predict, instead, a devaluation of the currency of the nation running the high budget deficit, and eventual "crowding out" of private investment.

According to Mundell, "Fiscal discipline is a learned behavior." To put it another way, eventually the unfavourable effects of running persistent budget deficits will force governments to reduce spending in line with their levels of revenue. This view is also promoted by Victor Canto.

The central issue at stake is the point of diminishing returns on liquidity in the investment sector: Is there a point where additional money is "pushing on a string"? To the supply-side economist, reallocation away from consumption to private investment, and most especially from public investment to private investment, will always yield superior economic results.

In standard monetarist and Keynesian theory, however, there will be a point where increases in asset prices will produce no new supply. A point where investment demand outruns potential investment supply, and produce instead asset inflation, or in common terms a bubble. The existence of this point, and where it is should it exist, is the essential question of the efficacy of supply-side economics.

Effect on tax revenues

U.S. federal government tax receipts as a percentage of GDP from 1945 to 2015 (note that 2010 to 2015 data are estimated).

Although the term "supply-side economics" may have been coined later, the idea was experimented with in the 1920s. Income tax rates were cut several times in the early 20s, in total cutting the average tax rate by less than half. Although those responsible for the cuts had claimed the cuts would increase tax revenue, this did not occur. Income tax revenue did not reach even close to 1920 levels until tax rates were returned to 1920 levels in 1941.[33][34]

Some contemporary economists do not consider supply-side economics a tenable economic theory, with Alan Blinder calling it an "ill-fated" and perhaps "silly" school on the pages of a 2006 textbook.[35] Greg Mankiw, former chairman of President George W. Bush's Council of Economic Advisors, offered similarly sharp criticism of the school in the early editions of his introductory economics textbook.[36] In a 1992 article for the Harvard International Review, James Tobin wrote, "[The] idea that tax cuts would actually increase revenues turned out to deserve the ridicule…"[37]

The extreme promises of supply-side economics did not materialize. President Reagan argued that because of the effect depicted in the Laffer curve, the government could maintain expenditures, cut tax rates, and balance the budget. This was not the case. Government revenues fell sharply from levels that would have been realized without the tax cuts.Supply side proponents Trabandt and Uhlig argue that "static scoring overestimates the revenue loss for labor and capital tax cuts",[39] and that instead "dynamic scoring" is a better predictor for the effects of tax cuts. To address these criticisms, in 2003 the Congressional Budget Office conducted a dynamic scoring analysis of tax cuts advocated by supply advocates; Two of the nine models used in the study predicted a large improvement in the deficit over the next ten years resulting from tax cuts and the other seven models did not.[40]

– Karl Case & Ray Fair, Principles of Economics (2007), p. 695.[38]

U.S. monetary and fiscal experience

Supply-side economists seek a cause and effect relationship between lowering marginal rates on capital formation and economic expansion. The supply-side history of economics since the 1960s hinges on the following key turning points:Reaganomics

Main article: Reaganomics

Reagan gives a televised address from the Oval Office, outlining his plan for tax reductions in July 1981.

In the United States, commentators frequently equate supply-side economics with Reaganomics. The fiscal policies of Ronald Reagan were largely based on supply-side economics. During Reagan's 1980 presidential campaign, the key economic concern was double digit inflation, which Reagan described as "Too many dollars chasing too few goods", but rather than the usual dose of tight money, recession and layoffs, with their consequent loss of production and wealth, he promised a gradual and painless way to fight inflation by "producing our way out of it".[41]

Switching from an earlier monetarist policy, Federal Reserve chair Paul Volcker began a policy of tighter monetary policies such as lower money supply growth to break the inflationary psychology and squeeze inflationary expectations out of the economic system.[42] Therefore, supply-side supporters argue, "Reaganomics" was only partially based on supply-side economics. However, under Reagan, Congress passed a plan that would slash taxes by $749 billion over five years. As a result, Jason Hymowitz cited Reagan—along with Jack Kemp—as a great advocate for supply-side economics in politics and repeatedly praised his leadership.[43]

Critics of "Reaganomics" claim it failed to produce much of the exaggerated gains some supply-siders had promised. Krugman later summarized the situation: "When Ronald Reagan was elected, the supply-siders got a chance to try out their ideas. Unfortunately, they failed." Although he credited supply-side economics for being more successful than monetarism which he claimed "left the economy in ruins", he stated that supply-side economics produced results which fell "so far short of what it promised," describing the supply-side theory as "free lunches".[44]

Krugman and other critics point to increased budget deficits during the Reagan administration as proof that the Laffer Curve is wrong. Supply-side advocates claim that revenues increased, but that spending increased faster. However, they typically point to total revenues[45] even though it was only income taxes rates that were cut while other taxes, notably payroll taxes were raised.[46] That table also does not account for inflation. For example, of the increase in revenue from $600.6 billion in 1983 to $666.5 billion in 1984, $26 billion is due to inflation, $18.3 billion to corporate taxes and $21.4 billion to social insurance revenues (mostly FICA taxes).[47]

Income tax revenues in constant dollars decreased by $2.77 billion in that year. Supply-siders cannot legitimately take credit for increased FICA tax revenue, because in 1983 FICA tax rates were increased from 6.7% to 7% and the ceiling was raised by $2,100. For the self-employed, the FICA tax rate went from 9.35% to 14%.[48] The FICA tax rate increased throughout Reagan's term, and rose to 7.51% in 1988 and the ceiling was raised by 61% through Reagan's two terms. Those tax hikes on wage earners, along with inflation, are the source of the revenue gains of the early 1980s.[49]

It has been contended by some supply-side critics that the argument to lower taxes to increase revenues was a smokescreen for "starving" the government of revenues, in the hope that the tax cuts would lead to a commensurate drop in government spending. However, this did not turn out to be the case on the spending side; Paul Samuelson called this notion "the tape worm theory—the idea that the way to get rid of a tape worm is [to] stab your patient in the stomach".[50]

Supply-side advocates like Wanniski counter that social and fiscal conservatives who supported the supply-side prescription on tax policy for this reason were misguided and did not understand the Laffer Curve.[51]

There is frequent confusion on the meaning of the term 'supply-side economics', between the related ideas of the existence of the Laffer Curve and the belief that decreasing tax rates can increase tax revenues. But many supply-side economists doubt the latter claim, while still supporting the general policy of tax cuts. Economist Gregory Mankiw used the term "fad economics" to describe the notion of tax rate cuts increasing revenue in the third edition of his Principles of Macroeconomics textbook in a section entitled "Charlatans and Cranks":

An example of fad economics occurred in 1980, when a small group of economists advised Presidential candidate, Ronald Reagan, that an across-the-board cut in income tax rates would raise tax revenue. They argued that if people could keep a higher fraction of their income, people would work harder to earn more income. Even though tax rates would be lower, income would rise by so much, they claimed, that tax revenues would rise. Almost all professional economists, including most of those who supported Reagan's proposal to cut taxes, viewed this outcome as far too optimistic. Lower tax rates might encourage people to work harder and this extra effort would offset the direct effects of lower tax rates to some extent, but there was no credible evidence that work effort would rise by enough to cause tax revenues to rise in the face of lower tax rates. … People on fad diets put their health at risk but rarely achieve the permanent weight loss they desire. Similarly, when politicians rely on the advice of charlatans and cranks, they rarely get the desirable results they anticipate. After Reagan's election, Congress passed the cut in tax rates that Reagan advocated, but the tax cut did not cause tax revenues to rise.[52][53]

Research since 2000

Supply-side economics proposes that lower taxes lead to employment

growth. Historical state data from the United States shows a

heterogeneous result.

Tax decreases on high income earners (top 10%) are not correlated with

employment growth, however, tax decreases on lower income earners

(bottom 90%) are correlated with employment growth.[54]

Passing these tax cuts will worsen the long-term budget outlook, adding to the nation’s projected chronic deficits. This fiscal deterioration will reduce the capacity of the government to finance Social Security and Medicare benefits as well as investments in schools, health, infrastructure, and basic research. Moreover, the proposed tax cuts will generate further inequalities in after-tax income.[55]Nobel laureate economist Milton Friedman agreed the tax cuts would reduce tax revenues and result in intolerable deficits, though he supported them as a means to restrain federal spending.[56] Friedman characterized the reduced government tax revenue as "cutting their allowance".

Bush tax cuts

Later analysis of the Bush tax cuts by the Economic Policy Institute claims that the Bush tax cuts have failed to promote growth, as all macroeconomic growth indicators, save the housing market, were well below average for the 2001 to 2005 business cycle. These critics argue that the Bush tax cuts have done little more than deprive government of revenue, increase the deficit, and worsen after-tax income inequality.[57] Following the release of the EPI report, though, growth remained strong and newer numbers disputed the conclusions of the report. The Bush administration pointed to the long period of sustained growth, both in GDP and in overall job numbers, as well as increases in personal income and decreases in the government deficit.[58] However, the claims by the Bush administration were made prior to the onset of the 2008 financial crisis.Prior to the American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 (ATRA), CBO estimated that allowing the expiration of the Bush tax cuts would raise $823 billion in revenue over the next 10 years relative to current policy, saving $950 billion (0.5 percent of GDP) when accounting for debt service. ATRA permanently extended the Bush tax cuts for households earning less than $400,000.[59]

The results of the tax cuts in the U.S. in 2001 and 2003 are mixed. While results show a temporary decline in tax receipts, they later recovered due to economic growth. In this analysis, it is difficult to discern the reason for the decreases in tax revenue because 2001 was the same year that the dot-com bubble burst. Total Federal Revenues in FY2000 were $2.025 trillion (in inflation adjusted dollars).[60]

In 2001, President George W. Bush signed the Economic Growth and Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2001. Rather than wait for the start of the new fiscal year, income tax rate reductions started on July 1, 2001. In addition, rebate checks were sent to everyone who filed a 2000 income tax return before October 1, the start of the new federal fiscal year.[61] Federal revenues in FY2001 were $1.946 trillion, $79 billion lower than in FY2000. More of the 2001 tax cut took effect at the start of FY2002, including cuts in the estate tax, retirement and educational savings.[62] Federal revenues in FY2002 were $1.777 trillion, $247 billion lower than in FY2000.

In 2003, President Bush signed the Jobs and Growth Tax Relief Reconciliation Act of 2003. Income tax rates were immediately reduced and rebate checks issued (without waiting for the new fiscal year).[63] Federal revenues in FY2003 were $1.665 trillion, $360 billion lower than in FY2000. Federal revenues in FY2004 were 1.707 trillion, $318 billion lower than in FY2000. Federal revenues in FY2005 were $1,888, $137 billion lower than in FY2000, but by 2006 revenue had completely recovered (in inflation adjusted dollars), with receipts at $2.037 trillion, $12 billion higher than 2000. The cumulative total of federal revenues less than in FY2000 for the fiscal years 2001–2005 was $1.142 trillion, with that amount expected to be recovered by 2011, with 2012 expected to produce an additional $400 billion in excess revenue over 2000.

Federal revenues include revenue from different taxes that were cut, stayed the same, or were raised. For example, the Social Security FICA tax rate stayed the same while the maximum income subject to the tax was increased each year, resulting in a tax increase for those earning more than the previous limit.[64] Social Security tax revenues increased each and every year. Including increasing tax revenues from taxes that stayed the same or were increased hides the magnitude of the revenue decrease in taxes that were cut. Income tax rates were cut and income tax revenues were lower than the FY2000 level each and every fiscal year from 2001 to 2005, a cumulative revenue decrease of $640 billion (measured in nominal dollars).

But, by 2006 revenues exceeded the 2000 level. Likewise Corporate income tax rates were cut and revenues were lower than the FY2000 level each and every fiscal year from 2001 to 2004. But, by 2005 the inflation adjusted take exceeded that of 2000 by over 20%, and by 2006 nearly 50% higher. Since tax cuts took after a stock market crash, and their effects were contemporaneous with both a recession and the 9/11 attacks, it's unclear whether temporary decreases in government revenue were the result of those cuts, or to other factors affecting the economy.

In 2006, the CBO released a study titled "A Dynamic Analysis of Permanent Extension of the President's Tax Relief."[65] This study found that under the best possible scenario, making tax cuts permanent would increase the economy "over the long run" by 0.7%. Since the "long run" is not defined, some commentators[66] have suggested that 20 years should be used, making the annual best case GDP growth equal to 0.04%. When compared with the cost of the tax cuts, the best case growth scenario is still not sufficient to pay for the tax cuts. Previous official CBO estimates had identified the tax cuts as costing the equivalent of 1.4% of the GDP in revenue. According to the study, if the best case growth scenario is applied, the tax cuts would still cost the equivalent of 1.27% of the GDP.[66]

This study was criticized by many economists, including Harvard Economics Professor Greg Mankiw, who pointed out that the CBO used a very low value for the earnings-weighted compensated labor supply elasticity of 0.14.[67] In a paper published in the Journal of Public Economics, Mankiw and Matthew Weinzierl noted that the current economics research would place an appropriate value for labor supply elasticity at around 0.5,[68] although Dr. Mankiw notes, "unfortunately, the academic literature on this topic is far from conclusive."

A 2008 working paper sponsored by the IMF showed "that the Laffer curve can arise even with very small changes in labor supply effects" but that "labor supply changes do not cause the Laffer effect."[69] This is contrary to the supply-side explanation of the Laffer curve, in which the increases in tax revenue are held to be the result of an increase in labor supply.[70] Instead their proposed mechanism for the Laffer effect was that "tax rate cuts can increase revenues by improving tax compliance." The study examined in particular the case of Russia which has comparatively high rates of tax evasion. In that case, their tax compliance model did yield significant revenue increases:

To illustrate the potential effects of tax rate cuts on tax revenues consider the example of Russia. Russia introduced a flat 13 percent personal income tax rate, replacing the three tiered, 12, 20 and 30 percent previous rates (as detailed in Ivanova, Keen and Klemm, 2005). The tax exempt income was also increased, further decreasing the tax burden. Considering social tax reforms enacted at the same time, tax rates were cut substantially for most taxpayers. However, personal income tax (PIT) revenues have increased significantly: 46 percent in nominal and 26 percent real terms during the next year. Even more interesting PIT revenues have increased from 2.4 percent to 2.9 percent of GDP—a more than 20 percent increase relative to GDP. PIT revenues continued to increase to 3.3 percent during the next year, representing a further 14 percent gain relative to GDP.[69]In 2003, a Congressional Budget Office study was conducted to forecast whether currently proposed tax cuts would increase revenues. The study used dynamic scoring models as supply side advocates had wanted and was conducted by a supply side advocate. The majority of the models applied predicted that the proposed tax cuts would not increase revenues.[40]

Criticisms

Supply side economics has been criticised for benefiting high income

earners. Graph shows the change in top 1% income share against the

change in top income tax rate from 1975–9 to 2004–8 for 18 OECD

countries. The correlation between increasing income inequality and

decreasing top tax rates is very strong.[71]

In 2012, a majority of economists surveyed rejected the viewpoint that the Laffer Curve's postulation of increased tax revenue through a rate cut would apply to federal US income taxes of the time in the medium term. When asked whether a “cut in federal income tax rates in the US right now would raise taxable income enough so that the annual total tax revenue would be higher within five years than without the tax cut,” none of economists surveyed by the University of Chicago agreed. 35% agreed with the statement "a cut in federal income tax rates in the US right now would lead to higher GDP within five years than without the tax cut."[73]

Critics of supply-side policies emphasize the growing federal and current account deficits, increased income inequality and the policies' failure to promote growth.[74]

In 2006 Sebastian Mallaby of The Washington Post quoted George W. Bush, Dick Cheney, Bill Frist, Chuck Grassley, and Rick Santorum misstating the effect of the Bush Administration's tax cuts.[75] On January 3, 2007, George W. Bush wrote an article claiming "It is also a fact that our tax cuts have fueled robust economic growth and record revenues."[76] Andrew Samwick, who was Chief Economist on Bush's Council of Economic Advisers from 2003 to 2004 responded to the claim:

You are smart people. You know that the tax cuts have not fueled record revenues. You know what it takes to establish causality. You know that the first order effect of cutting taxes is to lower tax revenues. We all agree that the ultimate reduction in tax revenues can be less than this first order effect, because lower tax rates encourage greater economic activity and thus expand the tax base. No thoughtful person believes that this possible offset more than compensated for the first effect for these tax cuts. Not a single one.[77]The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) has estimated that extending the Bush tax cuts of 2001–2003 beyond their 2010 expiration would increase deficits by $1.8 trillion over the following decade.[78] The CBO also completed a study in 2005 analyzing a hypothetical 10% income tax cut and concluded that under various scenarios there would be minimal offsets to the loss of revenue. In other words, deficits would increase by nearly the same amount as the tax cut in the first five years, with limited feedback revenue thereafter.[79]

Occasionally a politician claims that tax cuts increase government revenue (for example Mitch McConnell in July 2010[80]) However, critics have countered that the Laffer Curve reflects the hypothesis that only cutting tax rates to the right of peak economic performance rate will increase revenues, and that cutting tax rates to the left of the peak rate will decrease revenues. They therefore argue that the increase in the deficit from the tax cuts (see above paragraph) shows that the past tax rates were to the left of the peak rate.[80]

The paradigm of a tax system which rewards investment over consumption was accepted across the political spectrum, and no plan not rooted in supply-side economic theories has been advanced in the United States since 1982 (with the exception of the Clinton tax increases of 1993) which had any serious chance of passage into law. In 1986, a tax overhaul, described by Mundell as "the completion of the supply-side revolution" was drafted. It included increases in payroll taxes, decreases in top marginal rates, and increases in capital gains taxes. Combined with the mortgage interest deduction and the regressive effects of state taxation, it produces closer to a flat-tax effect. Proponents, such as Mundell and Laffer, point to the dramatic rise in the stock market as a sign that the tax overhaul was effective, although they note that the hike in capital gains may be more trouble than it was worth.

Cutting marginal tax rates can also be perceived as primarily beneficial to the wealthy, which commentators such as Paul Krugman see as politically rather than economically motivated.[81]

The specific set of foolish ideas that has laid claim to the name "supply side economics" is a crank doctrine that would have had little influence if it did not appeal to the prejudices of editors and wealthy men.[82]The economist John Kenneth Galbraith wrote, "Mr. David Stockman has said that supply-side economics was merely a cover for the trickle-down approach to economic policy—what an older and less elegant generation called the horse-and-sparrow theory: If you feed the horse enough oats, some will pass through to the road for the sparrows."

Post A Comment:

0 comments: